It’s a terrible idea to begin a story by telling the reader how much you do not like the story, yet that’s what I’m doing.

I do not want to write this piece. At all. I’ve already written the story and thrown it away more times than I can remember.

But I feel a need to write about it. It was a complex time, and writing is how I process those times. My inability to finish this story has become an obstacle stopping me from writing other projects. I need to break through it.

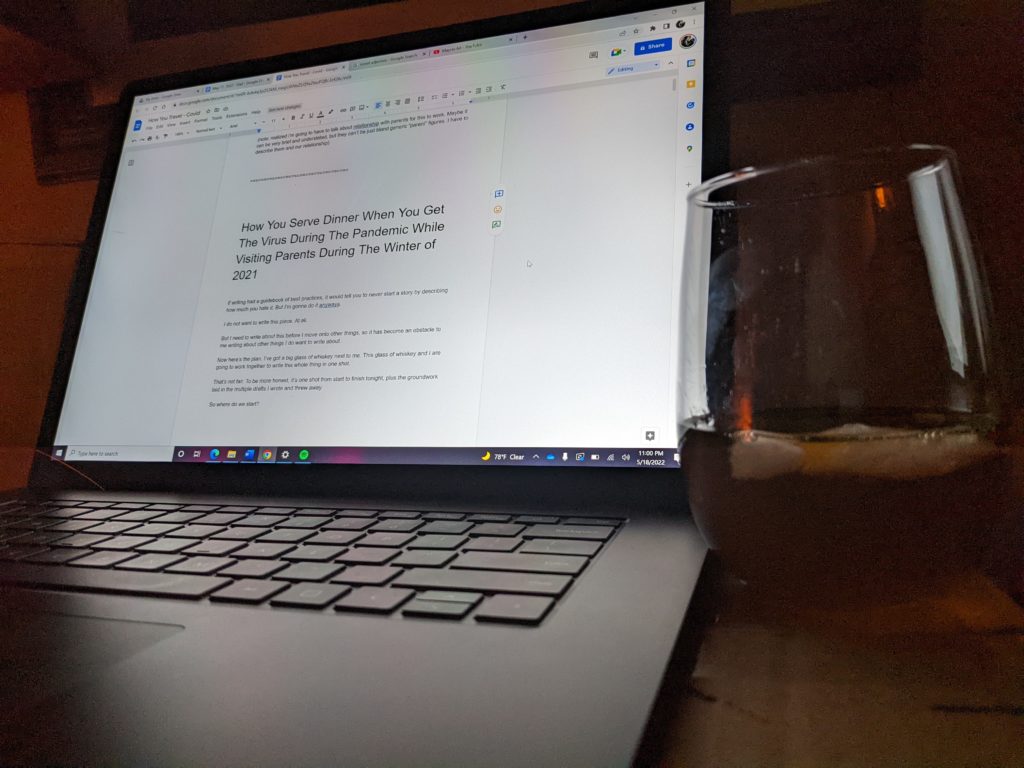

Here’s the plan. I’ve got a big glass of whiskey next to me. This glass of whiskey and I are going to work together to write this whole thing in one shot.

Or at least, it’ll be one shot helped by the ideas from my many previous drafts.

So where do we start?

The glass of whiskey just told me that we should start with setting.

It’s May 15, 2022 and you’re in a guest bedroom at Dad and Mom’s house in Texas. You’ve been living there for the past two months.

This is great because you haven’t seen them often lately, and you want to spend as much time with them as you can because Dad is dying of cancer.

He has a form of cancer that’s treatable but not curable.

That prognosis felt okay for the last sixteen years when he was well enough to build a woodworking shop in the garage, take cruises through the Mediterranean, and visit you to explore the Mojave Desert. The prognosis feels less okay now that he’s bedridden with a catheter, moaning through the night and physically unable to tell us what hurts.

You didn’t move back here for this. That was a coincidence. You moved back here for a job, and it just happened to line up with when he decided to end treatment because it was clear nothing was working anymore. Then, he deteriorated rapidly.

This is not a good time, but it’s still kind of good, ya know? It is a privilege to be here for him and for Mom at this time in the cycle of your lives. Like I said, you’ve seen them less than once a year recently. But funny enough, this is already the second time you’ve seen them this year.

You visited in late 2021/early 2022. That time had its own troubles. That’s the time you brought the virus into the home of your cancer-patient father.

You think about that a lot these days. What would have happened to him if he caught the virus? Survival rates overall are high, sure. But bone marrow produces white blood cells, so what’s the survival rate for a seventy year-old man when cancer has eaten eighty percent of his bone marrow? Just getting the basic flu sends him to the ER.

These days are bad. But it’s not as bad as it would have been if he had to say his goodbyes through a video call on a tablet while he laid alone in a hospital bed gasping for air.

Sorry, I’m losing focus. Let me back up and tell this story.

The hero of this story is a pillow. You intentionally place it in front of the door to block your path. The villain is something so small that you can’t even see it.

The date is December 31, 2021. All day, you’ve been sitting alone in your room playing Monster Hunter and watching Seinfeld on Netflix.

Now it’s dinner time. Mom ordered tacos.

Here’s the text conversation from the group text with you, Mom, and Dad:

Mom 5:38pm: Ok it’s here my Jed order is by the coke. Dads isn’t the bag. Dad first?

Dad 5:39pm: Ok. I’ll get mine and let you know when I’ve retreated.

Dad 5:41pm: Done

Dad 5:41pm: Next

You 5:42pm: Mom are you all clear for kitchen stuff? I think it’s a good idea for me to always go last.

Mom 5:54pm: Yes.

You 5:54pm: Ok *thumbs up* I’m gonna go out.

You, Mom, and Dad have been isolating in separate rooms since your test showed positive on December 30. Meal times have become an intricate choreography.

You head for the door but then you see that pillow. You stop.

You take a moment to review what you need to do.

Wash hands. Put on mask. Hold breath while in the hallway passing Mom’s room. Grab Styrofoam container with tacos. Grab drink from fridge. Grab fork from drawer. Get back to room.

Good. That leaves only two surfaces to disinfect. You can do this with less than thirty seconds outside of the room if you really focus.

Good. That leaves only two surfaces to disinfect. You can do this with less than thirty seconds outside of the room if you really focus.

You wash your hands and put on your mask. You go back to the door and stare at the pillow, questioning if you’ve missed anything. You haven’t. You move the pillow and go out.

You 6:04pm: I’m back in my room

Took far longer. Plan fell apart when you couldn’t find bottle opener for the beer.

Is that all it took? Did you spend too long in the kitchen, letting your infected breath spread like an aerosol spray?

You won’t know for a few days, so you head back to your room, eat, and then listen for anything resembling a cough or wheeze coming from Mom or Dad’s room.

Intermission

It’s time for intermission. Go ahead and hit the can or grab a snack. I’ll be here when you get back.

I said I’d write this in one night, but I didn’t. It’s the second night now–May 16, 2022–so my whiskey and I are starting again from here.

It looks like last night I was writing about how confusing things are during a pandemic. Should you disinfect every surface? Did you spend too long in the kitchen? Does that even matter?

Mom says holding your breath when you walk by her room is overboard. You’re fine with that. The time for overboard has come, so you decide to do all of the things which have evidence pointing towards helping.

You and your parents were fully vaccinated already. (1)

You all take turns spending time lounging outside to get Vitamin D. (2)

You keep Clorox wipes on the counter to scrub every surface after you touch it. (3)

You all wear masks any time you’re in communal areas. (4)(5)(6)(7)(8)(9)

When you read about pandemics in history books, it’s all statistics and symptoms and doctors wearing pointy nose masks.

The history books don’t capture how confusing it is.

Mom is developing a cough but no other symptoms. She tested negative with the at-home test. Should you still be worried? It’s confusing.

Cancer has eaten through Dad’s immune system, but he is vaccinated. What does that mean for his protection level? It’s confusing.

If he gets it, at what point do we take him to the hospital? Let’s make a plan now while we’re clear-headed. When he gets a fever? When he sniffles?

Dad says it should be when he feels it in his lungs. You think it’s probably too late by that point, but you also know that taking him to a crowded emergency room carries its own dangers.

So what should you do? It’s confusing.

It’s today again, now. May 16, 2022. About six months after you got the virus. Five months after you flew back to Thailand. Two and a half months after you had the first interview for your new job. Two months after you flew back to Texas.

Today, May 16, Dad cannot leave the bed anymore. Mom tried to give him water. He couldn’t reach for the glass and coughed horribly after drinking. He can barely speak, so you researched enlarged keyboard apps for his tablet so he could communicate by typing. Mom doesn’t believe he has the motor function to even do that. She’s probably right.

It all happened so fast. First he was getting around fine, then he needed a walker. The walker was too wide for the bathroom, so you bought him a thin walker. By the next day, he couldn’t muster the strength to use it, so Mom got him a wheelchair. By the next day, he couldn’t get out of bed to be in the wheelchair.

You stop writing. You look around the room and don’t see your phone. Adrenaline flares. You throw the covers off your bed and dig through piles of unfolded clothes on the floor, but you can’t find it.

The bathroom. That’s where you last saw it. You sprint over, and there it is. Enter your password. Check messages. No messages from Mom asking you to help pick up Dad from the floor again. You catch your breath and calm down.

Now it’s December of 2017. You flew in from your newspaper job in California to visit Mom, Dad, and your sister. On one of the days, you go with Dad because he volunteers to help restore houses damaged by Hurricane Harvey.

You walk into the damaged house and feel lost. He walks into the damaged house and knows how to fix everything. The walls, the wiring, the water.

He was an engineer his entire life. Growing up, you didn’t understand why people hired plumbers or electricians or mechanics. Why didn’t they just have their dad fix those things? Your Dad could fix anything.

Now it’s 1996. The Red Wings are playing the Avalanche in the NHL playoffs. You’re 10 years old. You and Dad are on the couch watching the game together.

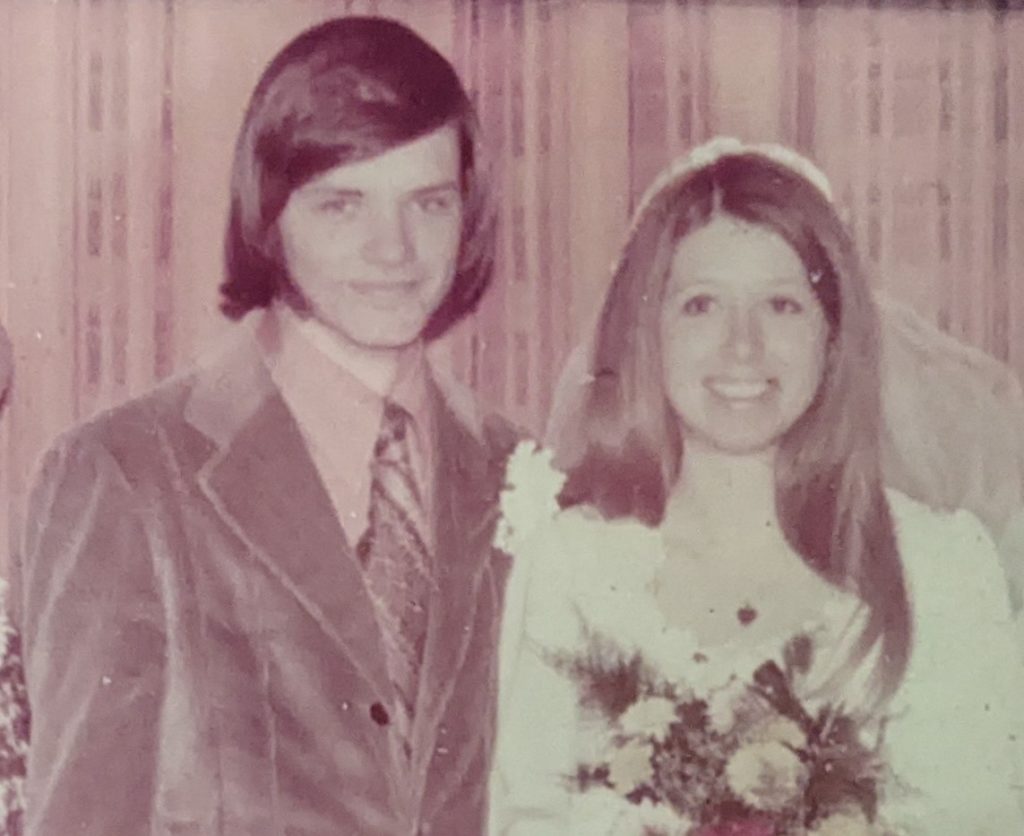

Now it’s 1970. You’re nowhere to be seen, but your young Mom leans out her window to see what the commotion is. Your young Dad with long brown hair throws a bucket of water at her. A relationship begins.

Another idea about pandemics that doesn’t come through the history books is how boring they are. Yes, there’s the punctuated moments of panic and confusion. But the mind can’t stay in that state all day. You ease into the situation, then become bored.

Your symptoms are minimal. Slight fever. Mild congestion.

Day-to-day, you spend your time playing video games, watching Seinfeld, and pressing your ear to the door to check if you hear any coughing.

At times, you grow complacent. At times, you forget that you’re one wrong breath away from a path that leads to saying goodbye to Dad through a video call and knowing you’re the one who infected him.

But you get through it.

On January 6, your test result comes back negative. You slowly step out of your room, and meet with Mom and Dad. You awkwardly stand together in the hallway and talk. You’re still masked and still distancing, unsure what normal is now. Does a negative test mean you’re not contagious? Probably, but it’s confusing.

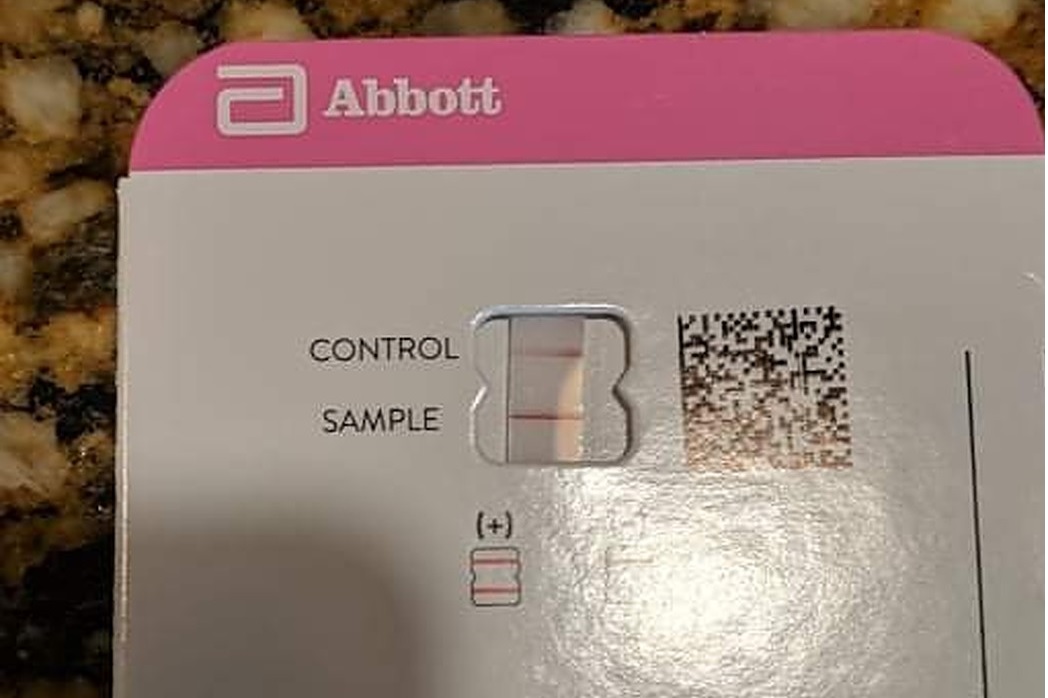

Within days, you return to life as normal. Within a month, you can no longer remember what the panic attack felt like when when you saw your positive test result and locked yourself in your room to punch your bed and to curse your choices and to tremble.

When your at-home test came back positive, Mom was picking Dad up from the hospital where he was getting blood transfusions. You didn’t feel sick, but you took the test because it was five days since you flew back and you wanted to be cautious.

When your at-home test came back positive, Mom was picking Dad up from the hospital where he was getting blood transfusions. You didn’t feel sick, but you took the test because it was five days since you flew back and you wanted to be cautious.

You immediately texted Mom to warn her. Then you told your brother who came from Louisiana to visit for the weekend. You told him that you’re scared because you’ve spent the past five days talking with Dad, eating with him, watching TV with him.

What did you expect from the conversation? That your brother had a magical power to look into the future and tell you that it was going to be okay? Well, he didn’t have that ability, and you were both left with uncertainty.

So the hero of this story is that pillow in front of your door, forcing you to remember what you need to do. And why.

Intermission

It’s now night three of this one-night story. It’s May 17, 2022. Dad died today just before three in the afternoon. This story wasn’t supposed to be about his death, but here we are.

It is sad, but a shade of sadness you’ve never seen before.

Intellectually, you understand that this was the right way to do things. Treatment had been going on for sixteen years. It wasn’t working. He was tired.

You understand it emotionally. Dad could fix anything, but in the past few days he couldn’t even spare the breath to express what he wanted. He couldn’t lift a finger to point. He was so frail.

It has been a difficult week. But there were moments when he broke through to remind you that this mind was still sharp even if his body was failing.

On one of his last nights, you said goodnight to him but then heard him mumbling as you walked away. You came back and put your ear close to his mouth. He said, “I’ll try not to misbehave.”

The last thing you heard him say was the day before he died. He was trying to speak but you couldn’t figure out what he was saying.

You said, “I’m so sorry, Dad. It’s very difficult to understand you right now.”

He said, “I understand you.”

Blended into this novel shade of sadness is a dash of happiness. You didn’t want to see him struggle anymore. He looked so peaceful when it was all done.

And the connection to the story here is that he died as he wished. In his bed at his home with family.

Though it may not feel so at the moment, this is the successful outcome from when you got the virus while visiting your parents in the winter of 2021.

He did not get infected and end in a hospital. Instead, he spent his final days at home after you had said everything to him and he had said everything to you.

It’s time for rest now, Dad. It’s time for peace.

It happened too soon. He always liked your writing and you were really looking forward to showing him this story.